By Irwing Lazo

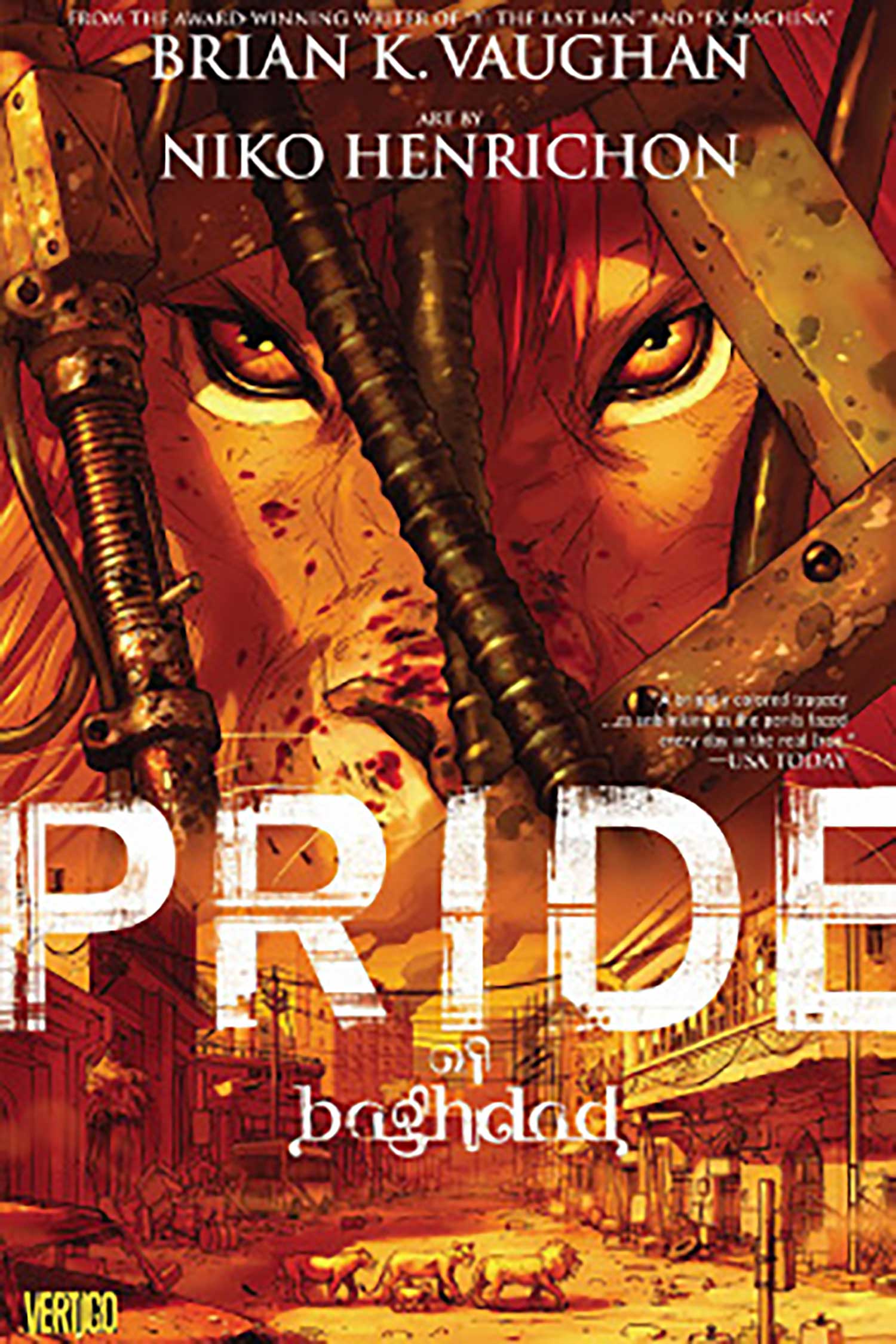

Frame from the graphic novel Pride of Baghdad by Brian K. Vaughan and Niko Henrichon

Now, I think things have gotten so bad inside Iraq, from the standpoint of the Iraqi people, my belief is we will, in fact, be greeted as liberators.

—US Vice-President, Dick Cheney (3/16/03)

One of the benefits of working in a school setting is that I get to learn from students, as they learn from me. Last fall, I heard one of our high school seniors discussing a book. I overheard the words “Baghdad” and “Saddam.” I was curious about the discussion. It turned out to be about a graphic novel based on the 2003 invasion of Iraq. I confided with the student about my tour in Iraq and we engaged in a short discussion about the book and my experience—another day of learning from one another.

Later, I read the graphic novel myself. Published in September 2006 by award-winning writer Kevin Vaughan and artist Niko Henrichon, Pride of Baghdad is a 136-page graphic novel inspired by true events. Four lions freely roaming the streets of Baghdad shortly after the 2003 invasion tell a story of survival, rapid change, and a first casualty of war, innocence.

Centered on a pride of lions that escaped the Baghdad Zoo, the author uses each lion as a point of view for this new freedom. Zill is the adult lion who has grown accustomed to zookeepers and mundane life at the zoo. Noor is the young lioness whom, although welcoming her new freedom, believes one ought to earn one’s freedom, rather than it being given by a foreign agent likely acting in their own interest. Safa is the oldest lioness who, given her prior life living in the wild, is apprehensive about her new status and prefers the stability of the zoo. Ali, the curious lion cub was born in the zoo where he always yearned to see a sunset like the ones his father painted in his imagination.

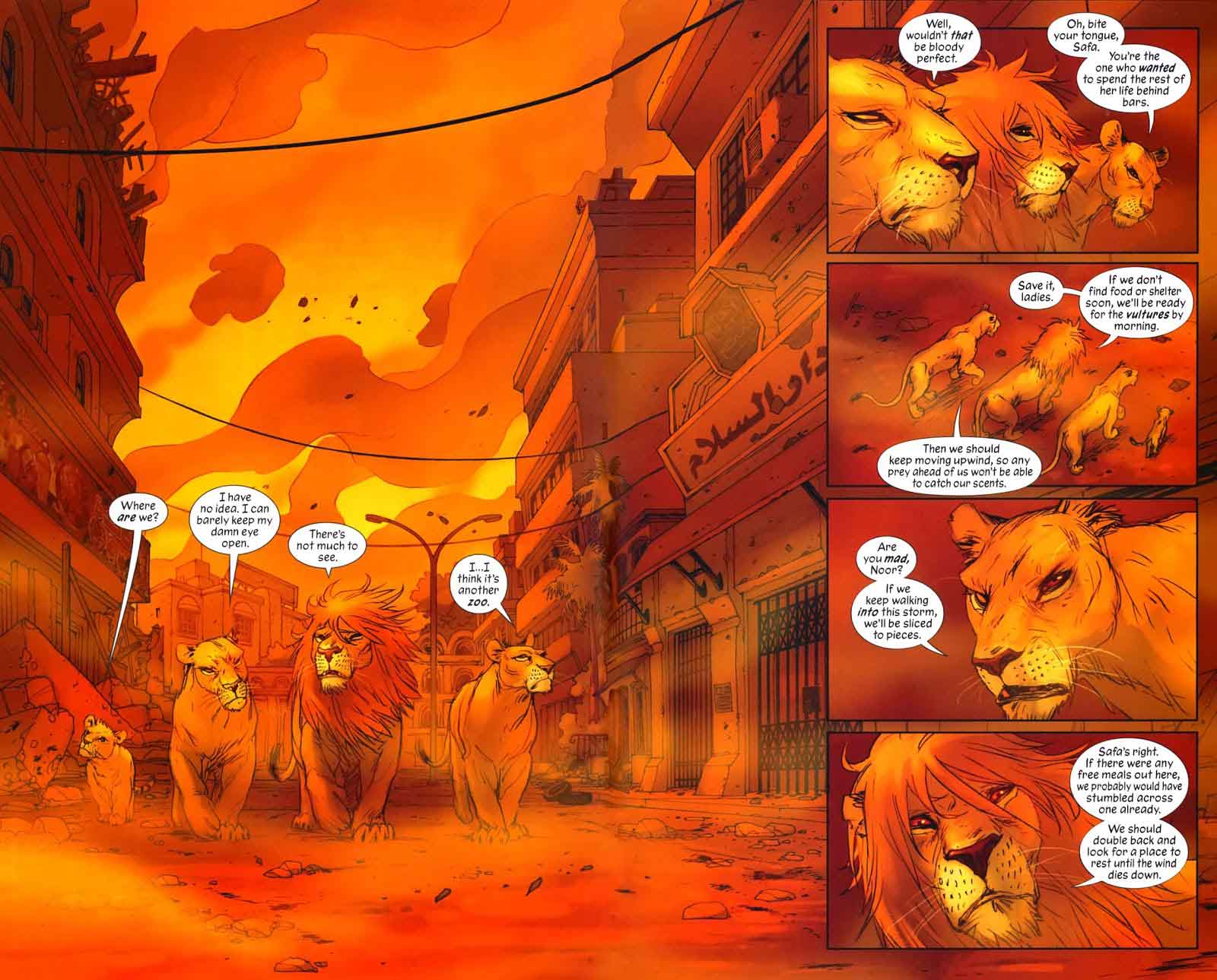

My first pride lived next to a hill, and in the evenings, I’d go to the very top of it. At the end of each day, I watched as the horizon devoured the sun, in slow steady bites, spilling its blood across the azure sky.

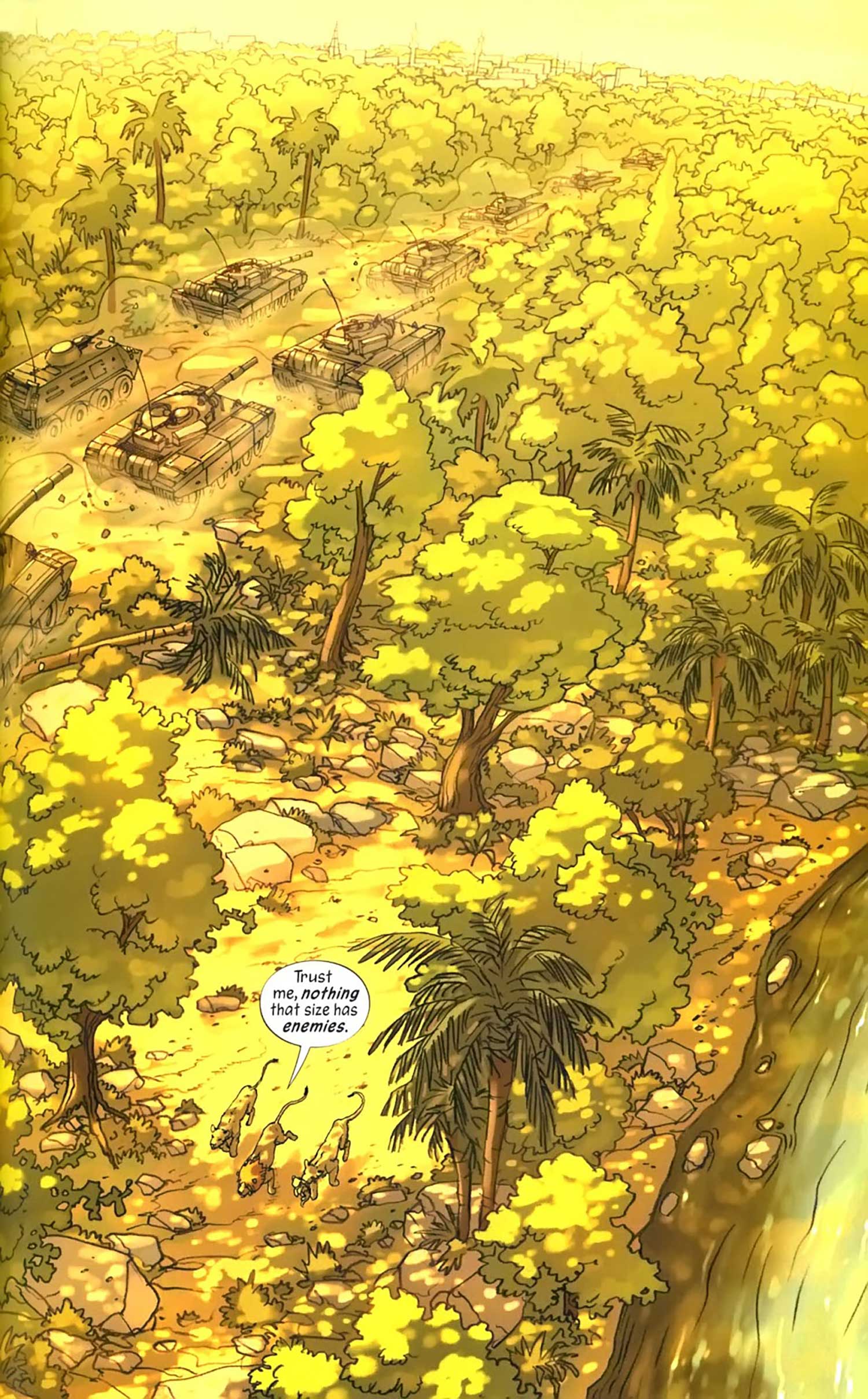

The plot is quite simple. The lions’ priority is to stay together and live. They do not have a strategic plan, nor do they care about the reasons for the invasion. However, the situation unfolding around them does not cater to family cohesiveness or survival. Buildings are on fire, zoo animals are running wild, and fighter jets circle the red skies. Questions emerge continuously throughout. There are clashing viewpoints as to what the zoo really was, who the keepers were, and whether life back at the zoo was better than now. For instance, amidst the chaos, the lions discover the lifeless body of a zookeeper. Zill suggests to the pack that they should eat the body, but Safa argues not to, because “they’re the ones who kept us alive.” Nonetheless, Zill reminds Safa that loyalty to a dead keeper won’t keep him from eating in order to survive. The allegory is clear: the Zoo represents Iraq before the invasion, where the Iraqis lived under the ironfist of Saddam Hussein and the Ba’ath Party, however under mostly stable conditions. On the other hand, the zookeepers can be seen as the Iraqi State to whom Iraqis of many ethnic and religious groups do not have a sense of loyalty to. Rather, loyalty is to family and tribe, as Zill demonstrates.

Frame from the graphic novel Pride of Baghdad by Brian K. Vaughan and Niko Henrichon

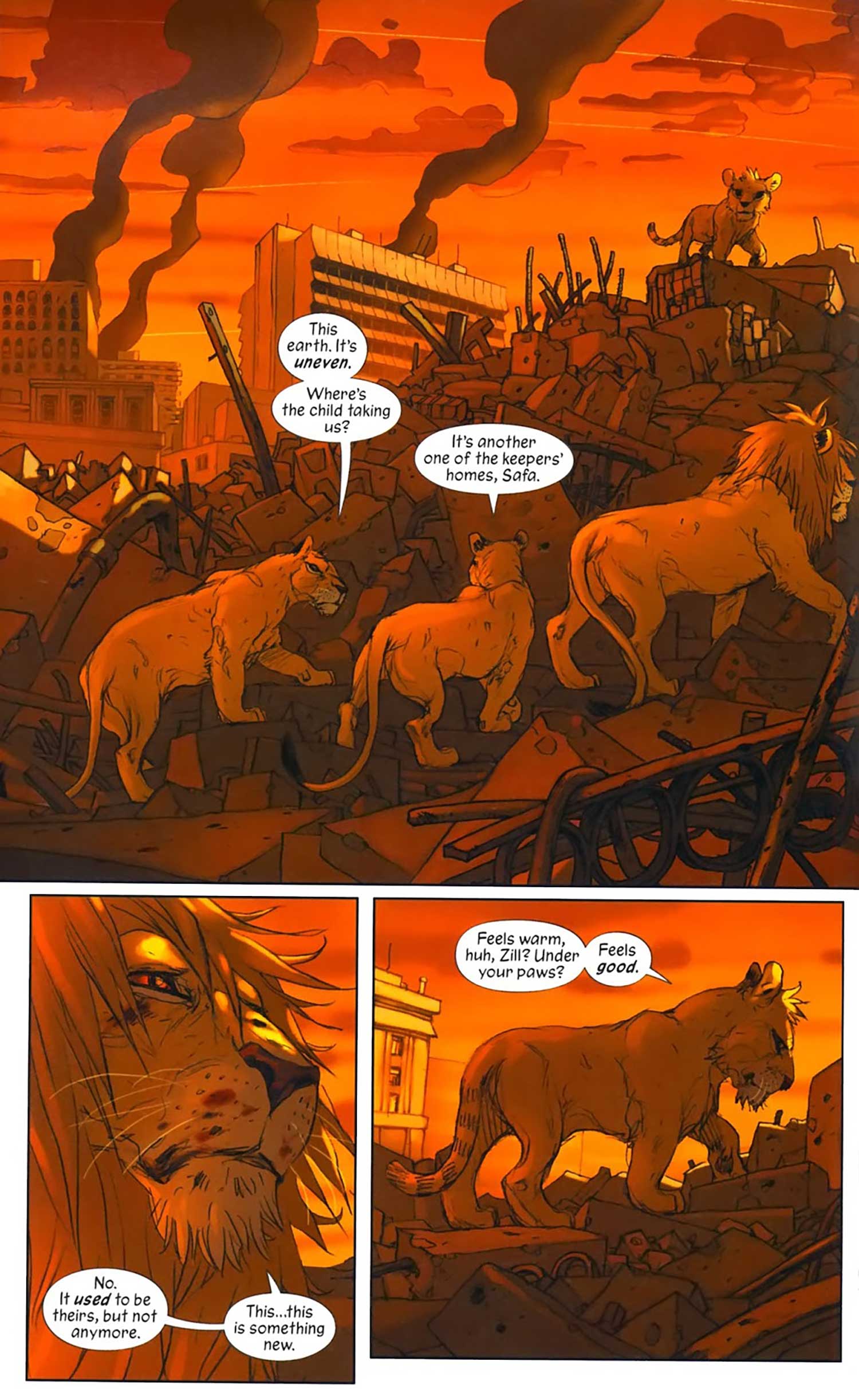

Tragically, the most innocent of the four lions, Ali, leads the pack to what he thinks are fireflies. They climb a pile of rubble hoping to reach a better view. As they get to the top, the sun is bleeding out into the horizon. “Is that a horizon?” asks the cub. Zill replies, “yes, yes it is!” Then Zill’s face cringes and drops to the ground. The fireflies were actually tracer rounds. Safa sees whom she thinks are “keepers” and decides to charge at them. But before she can reach them, rounds cut through her like water through a strainer. Noor and Ali suffer the same faith.

Frame from the graphic novel Pride of Baghdad by Brian K. Vaughan and Niko Henrichon

In a 2006 interview, author Kevin Vaughn said:

"I pitched the book way back in 2003, at the height of Dixie Chicks paranoia, when even asking questions about the war was seen as treasonous, so I’m very grateful to Vertigo [comics publisher] for being so supportive of an overtly political story about a conflict that’s still ongoing,” Vaughan said. “No matter what other projects I write down the line, Pride of Baghdad will probably always be the work I’m most proud."

It is worth noting that when Pride of Baghdad was published, the Iraq war was in its third year. By then, in addition to evolving into a protracted war, Iraqi society had developed into a full blown sectarian war. What’s more, lack of evidence for weapons of mass destruction and collusion between Al Qaeda and Saddam (the chief reasons for the invasion, of course) caused support for the war at home and abroad to decline. Unlike early years, by 2006, criticism of the war was more accepted, even mainstream.

Overall, the novel is intriguing, well written, and the graphics are quite amazing. My only criticism is that the author depicts the lions as being conflicted about the war. In fact, the Iraqi people were very clear from the beginning that they did not want to be invaded. Polling organizations have carried out many opinion surveys in Iraq since March 2003. These polls, including those sponsored by the US and UK governments, have clearly shown that Iraqis have been very critical of the presence of foreign forces in their country.

March 20, 2018, marked the 15th anniversary since the Bush/Cheney administration proclaimed the U.S. would be greeted as liberators of Iraq. More farcical words could not have been said (perhaps Ronald Reagan’s 1985 dedication of the Space Shuttle Columbia to the Taliban is a close rival: “these gentlemen are the moral equivalents of America's Founding Fathers”). No one faults Cheney for being a failed Nostradamus, but it’s clear he knew better than to invade Iraq. In his own words, during a 1994 C-SPAN interview, Cheney was asked why the US did not take Baghdad during the first Gulf War:

Because if we’d gone to Baghdad we would have been all alone. There wouldn’t have been anybody else with us. There would have been a U.S. occupation of Iraq. None of the Arab forces that were willing to fight with us in Kuwait were willing to invade Iraq.

Once you got to Iraq and took it over, took down Saddam Hussein’s government, then what are you going to put in its place? That’s a very volatile part of the world, and if you take down the central government of Iraq, you could very easily end up seeing pieces of Iraq fly off: part of it, the Syrians would like to have to the west, part of it — eastern Iraq — the Iranians would like to claim, they fought over it for eight years. In the north you’ve got the Kurds, and if the Kurds spin loose and join with the Kurds in Turkey, then you threaten the territorial integrity of Turkey.

It’s a quagmire if you go that far and try to take over Iraq...

So what changed between 1994 and 2003? Only Cheney knows. What we do know is that Iraq, prior to the 2003 U.S. invasion, did not experience the level of carnage that has now become routine. According to the most complete research on suicide bombing done by the University of Chicago’s Project on Security and Threats, before 2003 suicide bombings in Iraq were extremely rare. In fact, the report indicates that despite there being suicide bombings in other parts of the Middle East there were no recorded suicide bombings in Iraq prior to 2003. However, since the invasion of Iraq, there have been a total of 2,208 suicide attacks (and counting). The zoo’s gates truly did open. They have not been closed since 2003.

The University of Chicago Project on Security and Threats. Number of suicide attacks in the Middle East between 1982 to 2013. Note, the first slope is the bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, 1983. Post 2001, suicide bombings go up exponentially.

On this 15th anniversary of the invasion, it is imperative to remember the pain and death that an unnecessary war continues to cause. We ought to ask critical questions of Power, because in the words of John Adams, “Power always thinks it has a great soul and vast views beyond the comprehension of the weak; and that it is doing God’s service when it is violating all his laws.”

Additional frames from the graphic novel Pride of Baghdad by Brian K. Vaughan and Niko Henrichon

The images in this article are permitted by the Fair Use of Copyrighted material for the purpose of education and nonprofit. The Copyright Act of October 19, 1976. This is the copyright law of the United States, effective January 1, 1978 (title 17 of the United States Code, Public Law 94-553, 90 Stat. 2541).

Sources and Further Readings

https://www.cbr.com/the-joy-of-pride-vaughan-talks-pride-of-baghdad/

https://www.globalpolicy.org/invasion-and-war/iraqi-public-opinion-and-polls.html

http://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/civilians/iraqi

http://www.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/meast/04/16/sprj.nilaw.baghdad.zoo/

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/empires-chain-reaction/

http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/22/opinion/dying-to-kill-us.html

Irwing Lazo is a writer and public school administrator living in Santa Cruz, CA. He served four years in the U.S. Marine Corps and deployed to Fallujah, Iraq as a Motor Vehicle Operator. After leaving the military, he attended college thanks to the Post 9/11 GI Bill receiving a Masters in Public Administration from San Francisco State University in 2017.